Have you ever found yourself stuck with all the work in a group project while your partner slacks off, claiming they just “aren’t good at it?” Have you ever had someone in your class pretend they can’t figure something out, letting others handle the task originally assigned to them? Those are some simple examples of weaponized incompetence—a term that’s been making waves recently. What does this term really mean? Why has it gotten so much attention lately, and how can it affect school culture, friendships, and even large demographics?

Weaponized incompetence is when someone intentionally pretends to be bad at something to avoid responsibility. Instead of figuring it out, they avoid responsibility and accountability to shift the burden of the task onto others. Some common phrases are “I’m just really bad at this” or “(so-and-so) is better at this.” By making it seem as though they’re genuinely unable to do something, they guilt-trip others into excusing them for not putting in any effort. This behavior may manifest in friendships, educational groups, intimate relationships, and even at home when siblings or parents dodge chores by claiming to be unable to do them properly.

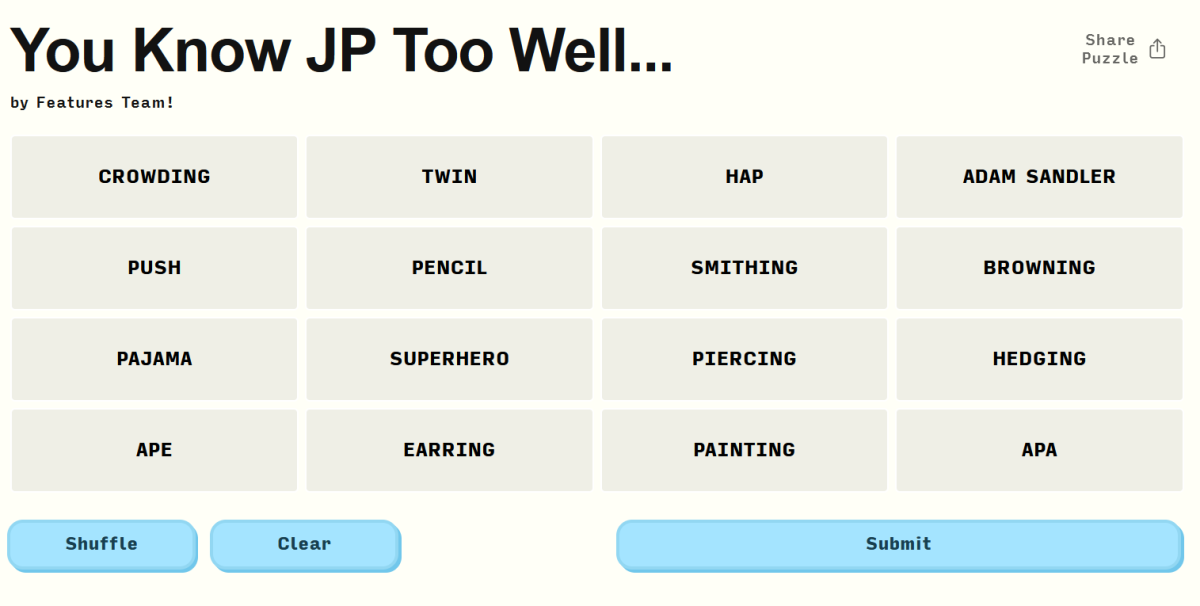

Weaponized incompetence is not exactly a new concept. Recently, people have become more aware of it as they notice patterns between oppression and weaponized incompetence. Especially with the rise of social media, like TikTok and Instagram, more discussions about fairness in relationships has led people to evaluate their relationships and speak about their experiences. Influencers and content creators have been sharing stories, memes, and videos about how this behavior plays out in everyday life and how it has played out in history. In the past, this behavior may have been dismissed as laziness or an innate lack of ability. However, the term “weaponized incompetence” highlights the idea that this isn’t just someone being bad at something—it’s a deliberate tactic used to manipulate others into performing more labor. At its core, this is someone trying to get through life with minimal effort, at the expense of and through the labor of others. This awareness has helped people recognize that some of their frustrations in their relationships with others stem from this very issue.

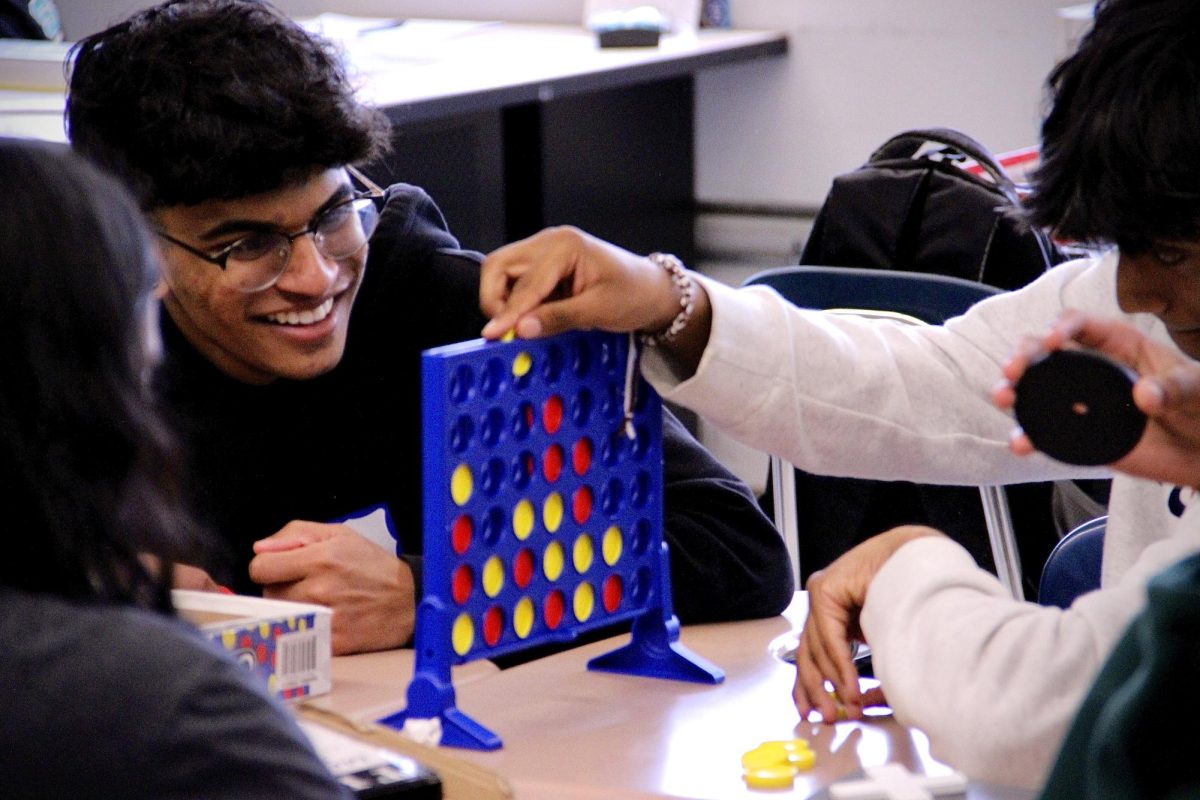

Our high school environment is one of the clearest places where weaponized incompetence plays out, especially in cases like group work or projects. How often have you been stuck with a group member who conveniently “can’t figure out” their part of the assignment, leaving you to do all of the work? You might even find yourself justifying it for them: “They’re probably just overwhelmed,” or even “I don’t want them to mess it up, so I might as well just do it.” But in reality, this is exactly how they want you to think because they achieve their goal of letting you do the heavy lifting. This behavior doesn’t just happen in group projects—it can also happen when your friend says, “I’m not good at this. Can you do this for me… again?” While helping out friends is great, it can become frustrating when you repeatedly have to do things for them or when they rely on you without putting in their own effort. Over time, this creates an unfair dynamic where one person feels burnt out and taken advantage of, leading to a decline in relationship satisfaction.

As more people become aware of weaponized incompetence, we can likely start to see shifts in how relationships—friendships, romantic relationships, or work partnerships—function. In a school setting, if students and teachers begin recognizing this behavior for what it is, they can call it out and handle it appropriately. Teachers can adjust group project dynamics, ensuring that everyone contributes equally. Students can feel comfortable setting boundaries in friendships and avoiding situations where they’re doing all the work. More importantly, recognizing weaponized incompetence can motivate people to take accountability. Students who might have previously used weaponized incompetence by saying they “aren’t good at” a task may start to realize that they need to at least try.

Recognizing and addressing weaponized incompetence can help us alter how we approach schoolwork, friendships, and responsibilities. Rather than letting someone get away with doing less under the guise of being “bad” at something, it’s better to encourage them to learn, grow, and contribute. Ultimately, calling out weaponized incompetence helps create healthier, more balanced relationships. So, the next time you hear someone say they “can’t” do something, remember that it might be worth digging a little deeper to find out if they really do need help or if they’re just avoiding responsibility.