Guilt Giving

February 16, 2023

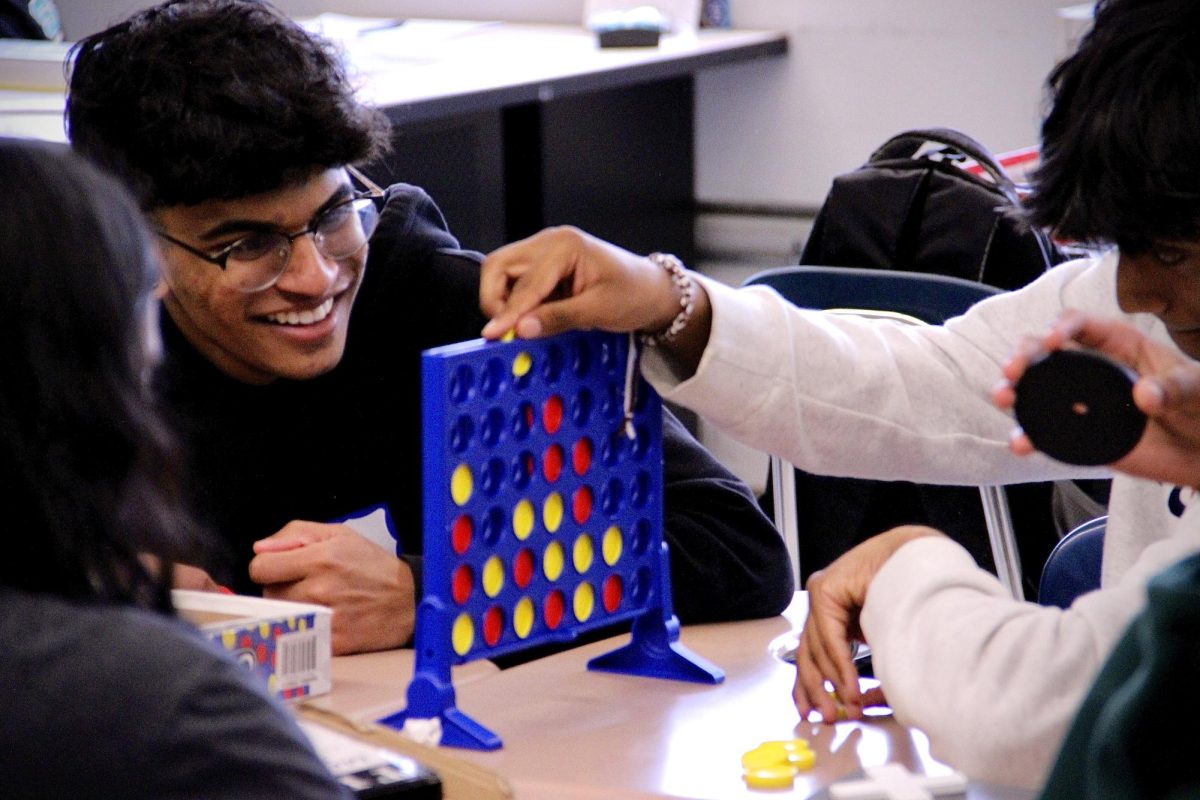

JP Stevens is a place where friends seem to know each others’ wants for any occasion- birthday and holiday alike. The friend who is always snacking would appreciate Goldfish, while the friend who is obsessed with coffee would love a Dunkin’ gift card. A personalized gift is an easy decision in these cases. But it becomes more difficult when the social charade of gift-giving adds yet another layer: the party favor. Also known as “return gifts”, party favors are given to guests to express gratitude for their attendance. Although the action of giving a gift may seem well-intentioned and harmless, figuring out what to present as a return gift can be too stressful to make the whole notion worth it.

My birthday was last month, and as customary, I was at Target (my happy place) to purchase return gifts for my friends. As I looked at the price tags, I had swirling thoughts of uncertainty that gnawed at the back of my mind like New York City subway rats. I kept wondering: was it good enough? Would they like the gift? Conversely, would the materialistic endeavor appear too cheap, as if I didn’t care about their well-being, even though that couldn’t be further from the truth?

A friend brought it to my attention that giving a return gift is appreciating someone for appreciating you, which, phrased like so, seems unnecessary. The people close to you already know you care about them, and vice versa. So why do people give return gifts?

Birthday celebrations were seen first in Ancient Egypt, where the Egyptians celebrated the day when one was “born as a god.” The Greeks were the first to give presents on birthdays, while the Romans began to celebrate birthdays similar to our modern day traditions, including the tradition of the return gift. When hosting a party, royal families would provide the guests with a bonbonniere, which is a box filled with candies or sweets. Aristocrats quickly caught on to this idea and did the same. This materialistic benefaction trickled down to join the sea of time, branching out to the public through rivers of knowledge and social etiquette.

Gift-giving is a form of exchange. This reciprocity norm is the belief that one will be shunned and lose respect if they do not repay the favor of a gift, making the person feel obligated to buy something of equal or greater value. Gifts are not simply items handed over from one person to another; they are conduits of social relationships and the central ideas of altruism and selflessness.

However, even when one gives with no expectation for something in return, they still possess an innate desire to receive; these thoughts are repressed but deeply influence how one reacts to a gift. If one feels that a present does not match the value of their relationship, they may feel frustrated and begin to believe that the other may not give much importance to their relationship.

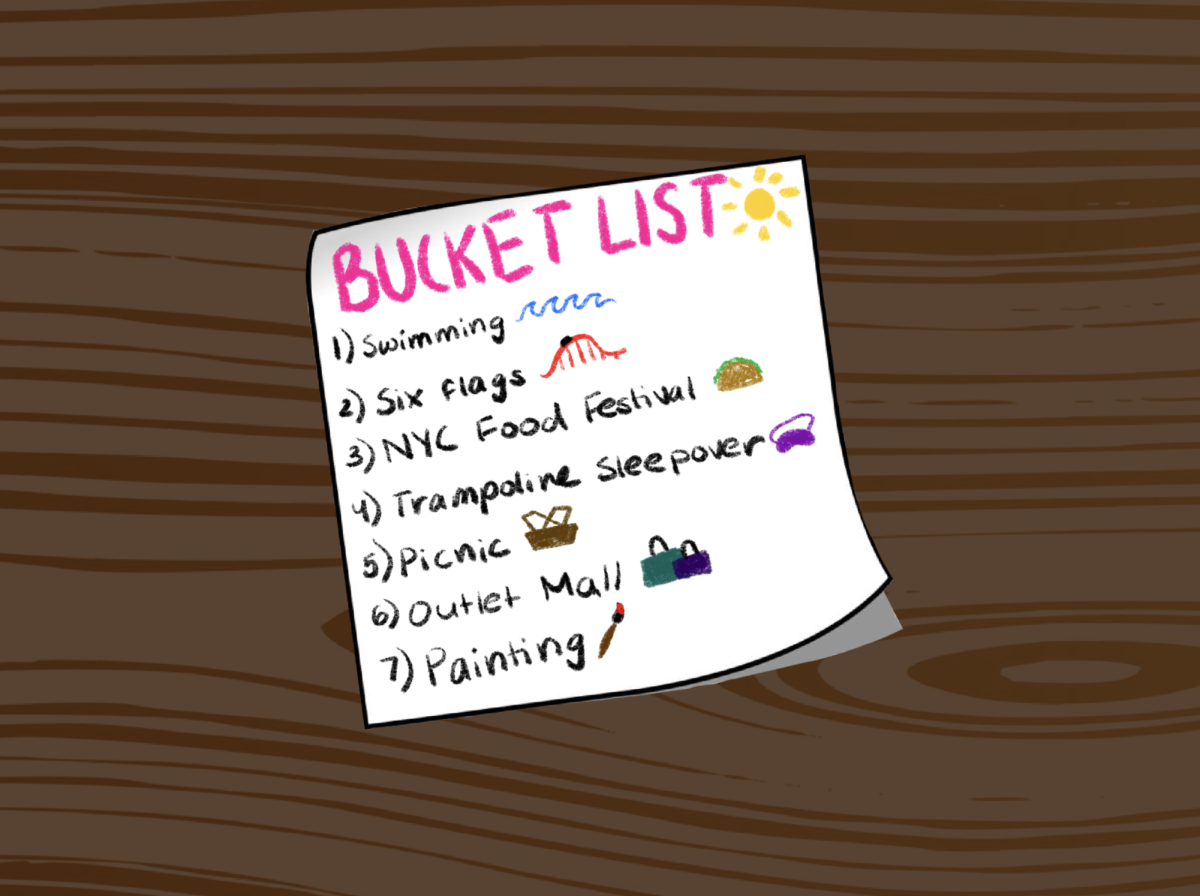

The adage “it’s the thought that counts” can be highly applicable here. For example, a friend gave me a drawing for my birthday. It was not something she put hours of effort into or spent hundreds of dollars for, but it was evident that she put a lot of thought into it. That leads me to believe that materialistic items do not always have value attached to them. Experience-based gifts, such as bowling with friends or taking a cooking class, are proven to strengthen relationships as they are associated with pleasant memories. This leads to a shared joy that is not guaranteed with material items.

People who feel compelled to give return gifts face pressure from the societal and reciprocal norms intertwined with altruism. Facing judgment, damaging existing relationships, and fear of diminishing social status are ultimatums for one to return the favor. Getting rid of the stigma that results from not buying a gift will bring experience-based gifts to the spotlight. It’s important to encourage people to change their mindset and remind themselves that true friends cherish their moments together, not the number of things you’ve bought them.